|

Tolerance in Buddhism, 6

by Ken and Visakha Kawasaki |

|||||||

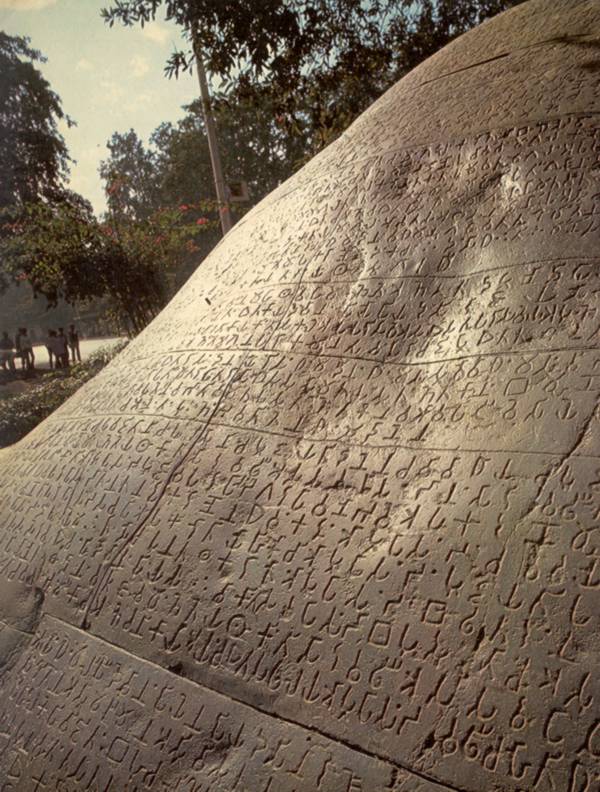

| King Asoka Buddhism began in northern India in the sixth century B.C.E., but its spread throughout the Indian subcontinent and to neighboring lands is due largely to the great Buddhist monarch, King Asoka, in the third century B.C.E. Early in his reign, Asoka was cruel and ruthless. He executed his brothers in order to seize the throne. At one point, his army fought an extraordinarily bloody battle against Kalinga. This victory created an empire greater than any India had known, but the bloodshed left the king disgusted and dismayed. Soon afterwards, King Asoka converted to Buddhism. Thereafter, he ruled wisely, justly, and with compassion. Although King Asoka is not well-known in the West, H. G. Wells praised him highly: "Amidst the tens of thousands of names of monarchs that crowd the columns of history. . .the name of Asoka shines, and shines almost alone, a star. . . . More living men cherish his memory today than has ever heard the names of Constantine or Charlemagne." After his conversion, King Asoka issued many edicts which he had engraved on huge rocks located throughout his kingdom and on pillars erected in places of significance in the life of Buddha. Asoka's edicts proclaim his reforms and the moral principles he recommended in his attempt to create a just and humane society. He declared that he regarded his subjects as his children and that their welfare was his main concern. Asoka carried out his reforms as a Buddhist, but he granted complete freedom of religion to all, urging others to practice their own religion with the same conviction that he practiced his. |

|||||||

| The edicts depict Asoka as a skillful and intelligent administrator and a devoted Buddhist. They everywhere are imbued with the Buddhist values of compassion, moderation, tolerance, and respect for all life. The Asokan state gave up the predatory foreign policy that had characterized the Mauryan empire and replaced it with a policy of peaceful co-existence. The judicial system was reformed in order to make it more fair, less harsh, and less open to abuse. Those sentenced to death were given a stay of execution to prepare appeals. Special occasions were regularly celebrated by granting amnesty to prisoners. State resources were used for public works, such as the importation and cultivation of medicinal herbs, the building of rest houses, the digging of wells at regular intervals along main roads, and the planting of fruit and shade trees. The hunting of certain species of wild animals was banned; forest and wildlife reserves were established; and cruelty to domestic and wild animals was prohibited. The government undertook to protect all religions and to foster harmony among them. |

|

||||||

|

Asoka ruled according to the ten duties of a king, as set forth in Buddha's teaching. These are:

|

|||||||

| Asoka treated his own daughter, Sanghamitta, with great respect. After she ordained as a Buddhist nun, he entrusted her to carry a sapling from the great Bodhi tree in Bodhgaya to Sri Lanka, which had just been converted to Buddhism by Asoka's own son, the monk, Mahinda. Today, as people search for a political philosophy that goes beyond the greed of capitalism, the rank intolerance of fascism and communism, and the delusions of tyrannical dictatorships, we ought to consider the Buddhist civil order that King Asoka established more than two thousand years ago. Never have we been more in need of tolerance, the virtue that makes peace possible, to help us replace, as Asoka did so many centuries ago, the culture of war with a nurturing culture of peace. |

|

||||||