by Ken and Visakha Kawasaki

|

|

| Ken and Visakha making an offering to Khmer monks in one of the refugee camp monasteries | |

Who were the refugees? They were survivors of the Cambodian genocide, in which a quarter of the country's population, almost 2 million people, were killed. The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, combined extremist ideology with ethnic hatred and a vicious disregard for human life to create misery, starvation, repression, and murder on an enormous scale.

Cambodia, like Laos, Thailand, and Burma was and is a predominately Theravada Buddhist country. Pol Pot himself learned to read and write in a temple school and spent several months as a novice, but he studied at a Catholic school before going for higher education in Paris (Cambodia was a French colony.), where he became a radical communist, espousing Maoist ideology.

Pol Pot, whose real name was Saloth Sar, left France without completing his studies and returned in 1953 to Cambodia, quickly becoming involved with the communist resistance to the Sihanouk government. In 1962, he was able to assume the leadership of the party, which became known as the Khmer Rouge.

Many observers believe that the secret bombing by the US Air Force of rural Cambodia along its border with South Vietnam was a key factor in the rise of the Khmer Rouge. From 1965 until 1975, American forces flew 231,000 bombing missions over Cambodia and dropped 2.75 million tons of munitions. It is estimated that these bombs alone killed between 40,000 and 150,000 Cambodians, both civilians and Khmer Rouge cadres.

In April 1975, the Khmer Rouge defeated the royalist army and assumed control of Cambodia. Renaming the country Democratic Kampuchea, they began a reign of terror, carrying out one of the most radical revolutions in history. They aimed to create a fundamental new order, a racially "pure" society, erasing the past, purging all foreign influence, and starting anew from "Year Zero." All institutions, including the "foreign" religions--Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism--were to be destroyed.

In the 1960s, there were approximately 65,000 monks and novices in Cambodia's 3,369 monasteries. Between 1975 and 1978 (when Vietnamese forces drove the Khmer Rouge from power), more than 85 per cent of the monks were executed. Those who survived were forced to disrobe and to work in the fields with the rest of the population. Monasteries were turned into storage centers, prisons, livestock barns, and torture centers. Images of the Buddha were decapitated, desecrated in other ways, or buried. In 1978, Yun Yat, Democratic Kampuchea's Minister of Culture, announced to Yugoslav journalists, "Buddhism is dead, and the ground has been cleared for the foundations of a new revolutionary culture." In 1979, there were fewer than 100 Khmer monks in the few temples which had been reopened.

The Vietnamese-dominated regime controlled the Cambodian government until 1988, but the Khmer Rouge remained active in the countryside, and both regimes continued to repress Buddhism. Refugees, including monks, continued to flee to Thailand. Two large camps, Khao I Dang and Site II, remained open on the Thai-Cambodian border throughout much of the 1980s.

After finishing our work in the Indochinese refugee camps, we returned to Japan and began teaching high school in Osaka. (We had left Japan in 1978, embarking on a year-long world tour, during which we discovered that we were Buddhist.) Each summer vacation, we returned to Thailand, going to temples, studying Buddhist art, meditating, and visiting friends. Although we hadn't worked in the Cambodian camps around Aranyaprathet, we went there a number of times to offer dana to the Khmer refugee monks and to learn more about their situation. We discovered that, since most of the organizations assisting the refugees were western and Christian, little attention was paid to the monasteries and monks. Food was not a problem, but the temples' lay supporters, being refugees themselves, had no way to offer robes or other requisites. Buddhist Relief Mission grew out of those experiences.

|

|

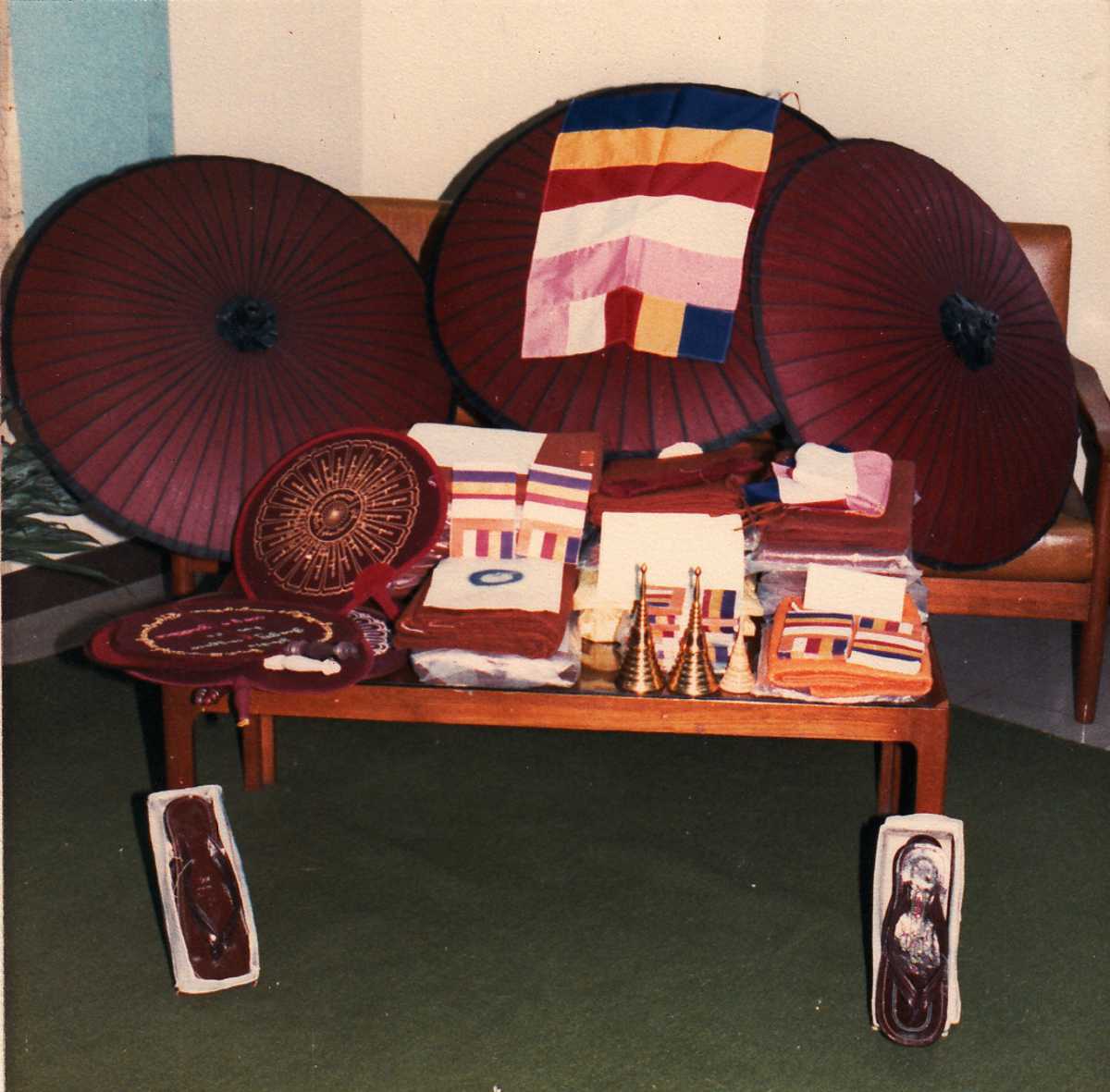

| The gifts from the Burmese monks, arranged in the UNHCR Office | |

Understanding what we were transporting, some officials must have quietly made allowances for the overweight luggage. We got everything to Bangkok without any difficulties. We ourselves had no time to return to the camp on the Cambodian border, so we immediately contacted the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and asked one of the field officers to help. He very willingly promised to deliver the gifts to the monks. We added two reliquaries containing arahat relics from a monastery in Kyaukse which we had received from U Ko Ko.

Several months later, the UNHCR field officer sent us a letter with several photos. He informed us that the monks in Khao I Dang were overwhelmed by the generosity of their Burmese brothers. In order to properly celebrate the donation, they had erected a small stupa within the monastery compound and organized a grand festival to pay respects as they enshrined the relics therein.

|

|

|

| The procession at the festival in Khao I Dang to enshrine the relics | ||

While we played but a minor role, for both the Burmese and the Cambodian monks it was an important occasion. Of course, the border camps are now all closed. A small number of refugees were resettled in third countries, but most, monks and lay, returned to Cambodia. The Burmese monks involved would have graduated long ago, but, we wonder how many of them were affected by the upheavals of 1988 and 2007?

Today, there are again more than 60,000 monks and novices in Cambodia, but the level of the Sangha remains low, due to the loss of an entire generation of learned monks. The first secondary school for monks did not re-open until 1993. This was followed in 1997 by a preparatory class for Preah Sihanouk Raj Buddhist University. The Buddhist revival in Cambodia has been led, not by the government, but by Cambodia's villagers, themselves victims of conflict and oppression. Without trained teachers and assistance from outside, it will take a long time for the Sangha to rise to its former level.

We hope there will be other opportunities for communication and encouragement between the Sanghas of Burma and Cambodia, for we know they have much to share and to learn from each other--lessons in suffering, oppression, impermanence, generosity, loving-kindness, and compassion.